Lang’s World: Saying Farewell to Henry Aaron, Who Changed Baseball, and the South

Lang WhitakerBeing a member of my elementary school chorus did not have a lot of added benefits. I only joined to get out of having to attend other classes, to be honest. Our yearly concert tour was limited to few school-wide assemblies and PTA meetings, and every once in a while we’d get asked to sing at a civic program or some sort of banquet. And that’s how I got to meet Hank Aaron.

This was in the ‘80s, though the exact year escapes me. The chorus from our school, which was not far from downtown Atlanta, was invited to sing the National Anthem at some sort of gala where the guest of honor would be Hank Aaron. Aaron had been retired for about a decade, but he was still royalty in Atlanta. I knew he’d been an incredible baseball player, who hit 755 home runs over the course of his career, the most anyone had ever hit. I didn’t know how important he’d been outside of baseball until a few years later.

On the big night, we lined up in the hallway outside the ballroom, then filed in and assembled in our assigned formation, just in front of the dais. We quickly discovered we couldn’t actually see Aaron, who was seated behind us at the main table. We sang whatever it was we were supposed to sing, then segued into a surprise verse of “Take Me Out To The Ballgame,” which drew a few appreciative chuckles from the audience.

And then we were done. To a smattering of polite applause, we turned and walked back into the hallway. It wasn’t until the door closed behind us that I realized we weren’t going to actually meet Hank Aaron. We were a cute diversion, we were just the entertainment, and our job was finished.

Then another door a few feet down the hall opened up, and Hank Aaron slipped out into the hallway with a smile. We all broke into a cheer, and he shushed us and held out both of his massive hands, his palms facing the floor, to remind us to keep the noise down.

Mr. Aaron ambled over to us with the hobbled gait of a former athlete, and we swarmed him, shaking his hands and hugging his legs.

“I just wanted to say thank you,” he told us. “You all did such a terrific job!”

In retrospect, I know now he was probably lying through his teeth. But at the time, for a kid who grew up in Atlanta, this was like receiving a blessing from the Pope himself.

Hank Aaron had retired long before I became a Braves fan, but his spectre still loomed over everything in Atlanta. Aaron owned restaurants and car dealerships, and was still involved with the Braves front office, so he’d pop up regularly at Braves games. But for most of us in Atlanta from the late ’70s on, Aaron was more of a legend than an active part of our sports fandom.

I learned about Henry Aaron as a kid, when I checked out a kid’s book about his life from the local library. It was geared toward children, and it gave me the basic framework of his life—born in Mobile, started in the Negro Leagues, made it to the majors, broke Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record.

It wasn’t until later that I understood just how towering a figure Aaron actually was, both in Atlanta history and in American history.

You can’t talk about Hank Aaron without starting with baseball, because Aaron was undeniably one of the greatest to ever play the game. Aaron hit a lot of home runs, but he wasn’t just a home run hitter. He batted over .300 for his career. Take away Aaron’s 755 career home runs, and he would still have 3,016 hits, which would put him 30th on the all-time hit list, ahead of players like Babe Ruth, Ken Griffey Jr. and Barry Bonds (including their home runs). Aaron played 23 seasons and went on the disabled list only once, for a broken ankle as a rookie. Aaron made the MLB All-Star Game for 21 years in a row. (LeBron has currently made 16 consecutive.)

Yet for those of us who grew up appreciating Aaron’s legacy, it was his skill at baseball that lifted him to a higher level, where we were able to appreciate his pride, his humility, his humanity. Just as important as his baseball career was his off-field impact. Aaron was the best player on the biggest team in the Jim Crow South. Whether he wanted to be or not, Aaron became a paradigm for the changing South.

Imagine reaching the zenith of your profession and thinking you might die because you were so exceptional at your job? Because that’s what happened to Hank Aaron. He played forever, piled up home runs, and all of a sudden found himself within reach of Babe Ruth’s record of 714 home runs. Aaron would later relay that his pursuit of Ruth’s record had been nothing short of harrowing. As Howard Bryant wrote last week for ESPN.com:

America asked him to do all of the things, and when he did them, he found himself at the top of his nation’s greatest sporting profession through the merit of statistics. In return, the FBI told him his daughter was the target of a kidnapping plot. For nearly three years he required a police escort and an FBI detail for himself and his family. He finished the 1973 season with 713 home runs — one shy of tying Ruth’s record — and believed he would be assassinated in the offseason. He had received enough letters to convince him so. He received death threats from 1972 to 1974 — all for doing what America asked of him.

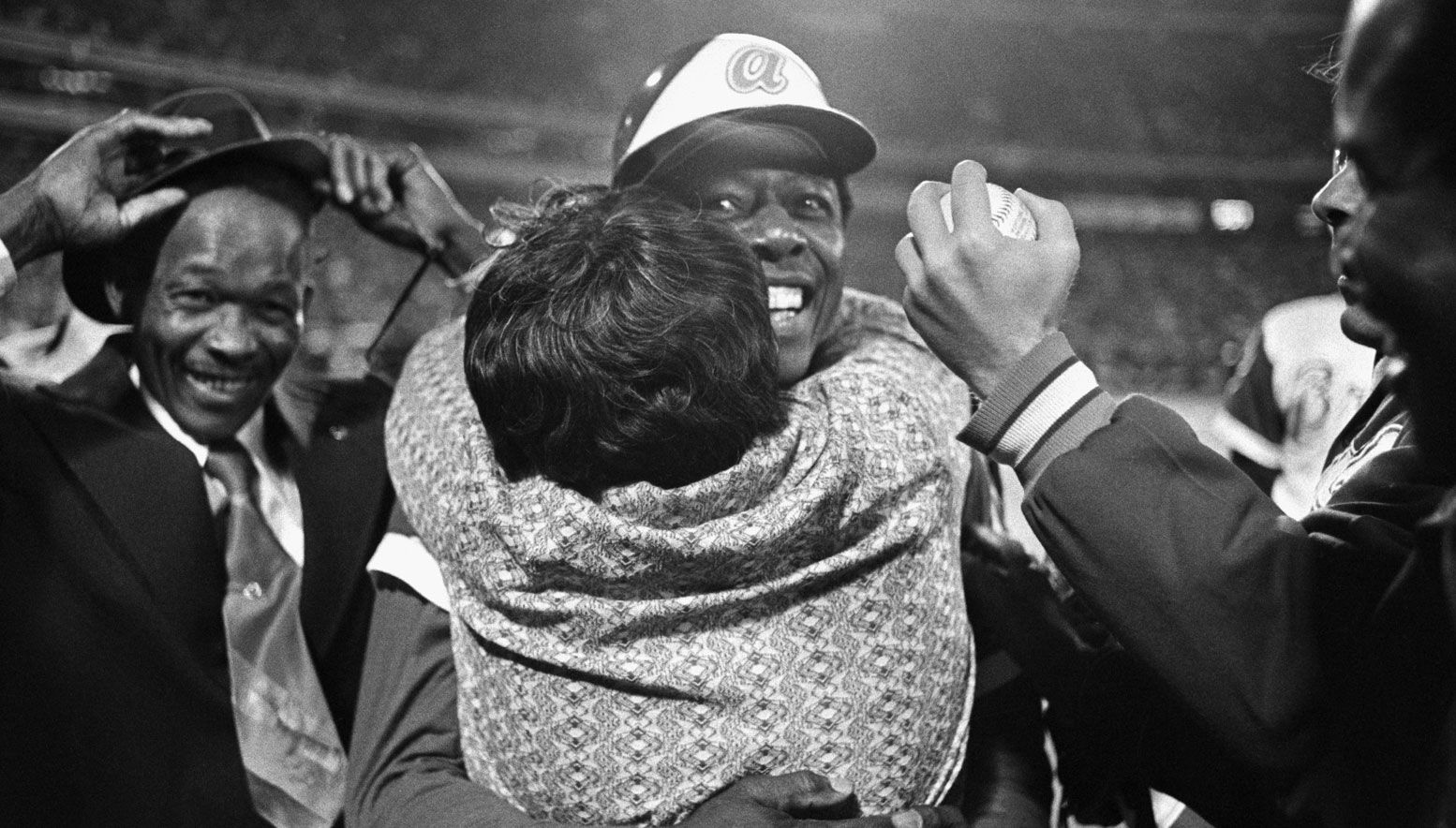

I’ve watched the clip of Aaron hitting home run number 715 a million times. And I can’t get over that Aaron thought that he might get killed, even while running the bases. If you watch here, as Aaron rounds second base and the two fans run on the field grab him to congratulate him, Aaron clearly aims an elbow at each of them, unsure of their intentions.

“What a marvelous moment for baseball … What a marvelous moment for the country and the world.”

RIP Hank Aaron, one of the greatest of all time.pic.twitter.com/kjrvSK19BM

— MLB Vault (@MLBVault) January 22, 2021

(By the way, when Aaron gets to home plate and everyone crowds around, the guy in the long beige trenchcoat holding a microphone is Craig Sager, who at the time was working as a reporter for a radio station in Florida. Sager ended up getting the first interview with Aaron after he broke the record.)

On the clip that has become the definitive record of the night, the legendary Vin Scully is calling the game for the Dodgers broadcast. As he says, “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta, and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South, for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol.”

What Scully didn’t say was that the all-time baseball idol who had just been dispatched was a white man. And in a South where so much was changing, thanks in large part to Dr. King, Aaron did his part to help lead the way. That home run was a remarkable moment in a remarkable life, but that one play did not define The Hammer. Hank Aaron didn’t ask to be thrust into the middle of the Civil Rights movement, but once he was there, he shined ever so brightly.

For a young white kid growing up in Atlanta, Aaron’s off-field impact and role in helping forever change the dynamics of the New South didn’t translate until I got a little older. When I got to sing for Hank Aaron, in that moment I was excited to meet one of the greatest baseball players who ever lived. In retrospect, I’m proud that I got to meet one of the greatest humans who ever lived.

Published on Jan 25, 2021

Related content